See my previous post about my endorsement of NDP candidate Diane Freeman for the riding of Waterloo.

I’ve in the past been an advocate of strategic voting.

I’ve in the past been an advocate of strategic voting.

Strategic voting, though, is very, very hard to get right. Even with all the polling data (which, for individual ridings, you don’t even have), you don’t really know what your neighbours are going to do election day. We have great tools like Vote Together and Three Hundred Eight, but I’m not convinced these are really enough information to base a good strategic vote on.

In strategic voting, you’re voting for a less-favourite party to keep out a hated party. Say you’re a big fan of the Greens, but your riding is a close race between the NDP and Conservatives, with the Greens trailing far behind. In this case, you might choose to vote NDP to keep the Conservatives out.

And this might be a rational choice. But are you sure the NDP and Conservatives are the only parties who have a chance at winning? How do you know that? Is that data reliable?

Vote Together, for the first time, actually did riding-specific polling for hotly contested ridings. Waterloo was one of them. They chose to use the results of their polling to say that people who didn’t want Peter Braid to take the riding again needed to vote Liberal.

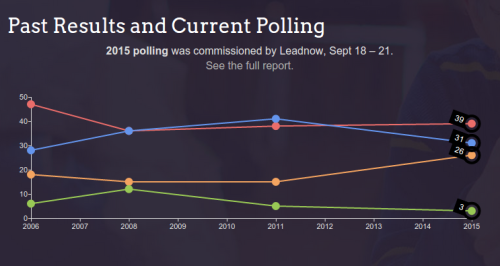

But if you look at the actual polling data, their margin of error is about 4%. They’ve got Chagger at a significant lead with 39% and Braid and Freeman fairly close at 31 and 26% respectively. This isn’t the case that the NDP have no chance of winning, even by their own polling. And the poll was taken a month ago.

Maybe now as the Liberals have the momentum local NDP support has fallen further, but do you know that?

Also important are other factors that may not show up in polling. In the last provincial election, and the by-election that proceeded it, this riding went to the NDP. Now the races and issues (and even the riding itself, now) are different, but what it does mean is die-hard NDP voters who might normally stay home because they think their party has no chance are emboldened and determined to come out and vote. And that Freeman, a popular city councillor, has more name recognition on the ballot than, say, a Chagger or a Walsh. The polls only ask about parties, not candidates.

Both the NDP and the Liberals have been making appeals to strategic voting, further muddying the waters. And the NDP has been the most egregious here, honestly. It’s a bit of a mess.

If you actually want to vote Liberal, that’s awesome. I’d usually agree with you. I actually prefer the Liberal economic plan and get really irritated by the populism of the NDP. But C-51.

If you were thinking of maybe voting NDP, at least in Waterloo, I don’t think strategic voting is a good reason not to. There are lots of other reasons why strategic voting’s bad for democracy, but here, now, I don’t think it even makes sense.

- Strategic Voting Doesn’t Work, Redux [My friend Bob Jonkman, running for the Greens in Kitchener—Conestoga]

Proportional Representation

While I know it won’t eliminate strategic voting, I do take heart that both the Liberals and NDP, who seemed destined to form the next government, barring a constitutional crisis, have promised to introduce some form of proportional representation before the next election. And, from my perspective, it can’t come soon enough.

While I know it won’t eliminate strategic voting, I do take heart that both the Liberals and NDP, who seemed destined to form the next government, barring a constitutional crisis, have promised to introduce some form of proportional representation before the next election. And, from my perspective, it can’t come soon enough.

My friend Paul is giving a talk with Fair Vote Canada about proportional representation, hoping to capitalize on the disappointment and disenfranchisement that inevitably follows a First Past the Post election. Come out to St John’s Kitchen on October 28th.

I think I’ve heard our system best described as: “Canadians don’t vote people into government, they vote people out of government”

Most of our voting choices right now are aligned with who we don’t want to take office, which isn’t really the way it’s supposed to be.